Fullerton Heritage is always looking for volunteers to help us on our many projects and we are happy to share our experiences and information with other preservationists. It's easy to reach us!

Design Guidelines for Residential Preservation Zones

Read MoreFullerton is home to several buildings and sites that have been placed on the National Register of Historic Places. To read more about the National Register, follow this link.

1900 Associated; in the Fullerton Arboretum on the Cal State Fullerton Campus

Listed: December 12, 1976

The Clark House is a unique example of the Eastlake style in Fullerton. Moved to the Fullerton Arboretum from its original location at 114 North Lemon Street in 1972, the house was subsequently restored over a number of years and has been given the name Heritage House. The original gabled roof had to be removed for the move; a new roof as well as a double chimney was reconstructed, identical to the original. The interior has been fully restored and refurbished with furniture and medical equipment of the era. A new ramp for handicap accessibility was constructed on the backside.

The Clark House is one of the oldest surviving homes constructed within the city's original townsite. This exquisite home provides a valuable memory of the appearance of a prominent residence in Fullerton around the turn of the century. The treatment of the exterior, the apparent exposure of construction details, the use of beveled and stained glass windows and the balanced format are indicative of the Eastlake style. The setting within the Arboretum has been designed to reproduce an authentic environment for the Clark home - like one that might have been seen in agrarian Fullerton in 1894.

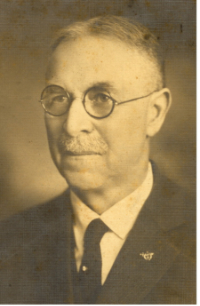

Dr. Clark was one of the most highly regarded individuals in early Fullerton. His house and office was a center for the medical, cultural, and civic activities of the community. He was active in a host of civic and social activities as well as a leader in the local medical profession.

Dr Clark had an active role with the city's incorporation and was elected to serve on the first city council in 1904. He was instrumental in having the Fullerton General Hospital constructed in 1913, at the northeast corner of Amerige and Pomona Avenues. His professional life reflects the growth of the region: it is estimated that during his career he brought into the world over 2,500 Orange Countians. His dedication to his profession is borne by the fact that he did not retire until he was nearly 80 years of age. The house on Lemon Street served as his residence and office for fifty-five of those years.

1201 W. Malvern

Listed: May 31, 1980

The Muckenthaler Cultural Center is the former estate home of Adella and Walter Muckenthaler, situated on a large lot that is elevated above Malvern Avenue. The main portion of the house is two stories in height, with one-story wings at both ends and a garage on the north side. The two-story portion, which includes a full basement, is an outstanding example of the Mediterranean variation of Spanish Colonial architecture.

This remarkable complex of buildings is complimented by an interior atrium, a stone gazebo with tile roof at the southeast of the house, and a wood arbor on the west side. The grounds around the home are an important part of the property, including the layout of landscaping, walkways and driveways.

The 7,600-sq.-ft. house along with its grounds is one of the most significant Orange County examples of Mediterranean residential architecture. The house's design was influenced by the 1915 Exposition in San Diego. The detailing of the two-story portion is exceptional, emphasized by the low-pitch tile roof, iron grill work, an octagonal solarium at the southeast corner with Palladian windows, the elaborate relief decoration around the main entry, and second floor balconies. Its reflection of an Italian villa is the result of trips taken by the Muckenthaler family to Europe, from where the impressive main interior staircase was imported.

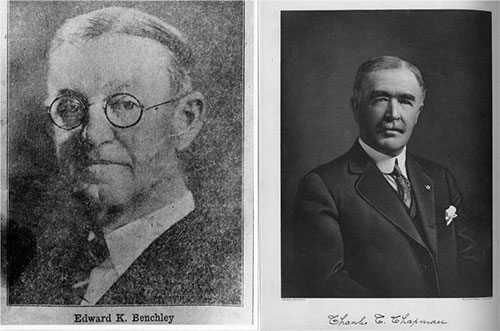

The architect was Frank Benchley, who designed many other significant structures in Fullerton, including the California Hotel, the Farmers and Merchants Bank, the second Masonic Temple, his father's Craftsman style home on Harbor Boulevard, and a well-preserved bungalow court on Pomona Avenue. The contractor, E. J. Herbert, also built the 1930 Santa Fe depot.

In 1918, Walter Muckenthaler married Adella Kraemer, a daughter of the wealthy Kraemer family of Placentia. In the early 1920s he purchased 80 acres of property that was part of the large Carhart ranch. The property extended southward from where the mansion was built in 1923, to Commonwealth Avenue. The majority of the land was devoted to groves of lemons, avocados and walnuts.

Walter Muckenthaler was a prominent person in the community. He served on the City Council and was very active in civic and business affairs from the 1930s through the 1950s. The 8.5-acre property where the house and its grounds are located was granted to the city in 1965, with the stipulation that it be used as a cultural center. Over the years a number of alterations have been made to the house to convert it to its specified use, but none has destroyed the original character-defining architecture. In the early 1990s, additional improvements were undertaken creating an outdoor stage and seating area on the south side of the house and a reception area along the west side. An adopted Master Plan for this property regulates and guides its future development.

201 W. Truslow Avenue

Listed: September 22, 1983

This building is one of the last remaining packing houses in Fullerton, where at one time as many as ten such plants lined the railroad tracts. It exemplifies the importance of the citrus industry in the growth of the city.

Constructed by the Union Pacific Railroad in 1924, the building was regarded as a very modern facility utilizing a conveyor system. It was initially leased to the Elephant Orchards of Redlands, Ca., which used the facility to pack its Valencia oranges under the Elephant Brand label. Later, in 1932, the Chapman family subleased the facility, and for over 20 years the Chapman's Old Mission Brand Valencia oranges were packed there. With the decline of the citrus industry in Orange County in the 1950s, the building ceased to be used as a packing plant; starting in 1957, the building has been used by a number of businesses for warehousing and manufacturing activities.

The building is one story, elevated over a full basement, which features a total of 23,500 sq. ft. of floor area. It is constructed of poured concrete posts and headers with hollow concrete tiles filling the spaces between spans. The exterior design of the building reflects the Mission Revival style that was so popular for non-residential buildings of that period. It consists of a parapet wall with Mission tile trim and a decorative firewall as architectural appendages. The most detailed design feature on the exterior of the building is the main entrance located near the southwest corner of the structure. Inside the structure wooden post and truss construction supports a saw-tooth roof design with skylights and ventilation on the north side -- the most identifying feature of the building.

The original hardwood plank flooring remains unaltered and is in good condition. The eight rectangular basement windows on the south and north sides of the building are presently boarded. An addition on the west side was built in 1971, but it blends well with the original building.

This building's past association with the packing, shipping, promotion and selling of the Old Mission Brand Valencia orange is extensive. The Valencia orange was the prize citrus product of Orange County and particularly Fullerton; indeed, the citrus industry was instrumental in the city's development and prosperity during the first half of the 20th century.

Charles C. Chapman played a major role in the development of the citrus industry. He was called the "father of the Valencia orange industry." This building is the only remaining structure directly connected with the business that made Chapman so well known. His home, ranch and first packing house have long been destroyed.

110 E. Wilshire Avenue

Listed: September 22, 1983

Designed by Anaheim architect M. Eugene Durfee, the Chapman Building is Fullerton's most outstanding commercial structure. Its design is a combination of the Chicago School of skyscraper architecture, as developed by Louis Sullivan, and a Southern California ethic.

The building is five stories in height with a basement; the basement extends approximately four feet under the public sidewalk on both Wilshire Avenue and Harbor Boulevard and is partially lighted by glass blocks in the pavement. The ground floor is open for retail space and includes a mezzanine level. A stairwell and elevator from the north entrance that is protected by a small marquee provide access to the upper floors. The design of the west and north façade of the building's upper levels - a classic placement and treatment of windows, the highly decorative cornice, and the use of masonry (terra cotta) for the exterior - reflects the Chicago School style. The east and south façades are painted brick with no ornamentation.

Constructed for Charles C. Chapman, Fullerton's first mayor and a well-known businessman, the structure's 65-foot height was the tallest in Orange Country when built in 1923. The 1920s in Orange County were prosperous, and the Chapman Building was the result of the unbounded optimism of the times. The original plans called for a three-story structure for a department store and offices; these plans were revised to add two more floors.

The Chapman Building is a good example of how commercial architecture in California in the early part of the 20th century reflected the background of its transplanted property owners. Instead of developing a native style, the architecture was usually imported from other parts of the country, just like much of the population. Charles Chapman began his entrepreneurial career in Chicago in the 1870s, leaving for California in 1894, when the Chicago Skyscraper style was at its peak. When the opportunity arrived, it was natural for Chapman to attempt to recreate this architecture in Fullerton. In using the style of Louis Sullivan, Mr. Durfee evidently "borrowed" some of the detailing from Sullivan's Bayard Building, constructed in New York in 1897.

In the building's early years, a department store occupied the first floor and the upper floors were offices. Starting in the 1950s, the property suffered a 30-year decline in use and maintenance with much of the building remaining vacant. In conjunction with the construction of a public parking structure at its rear, the Chapman Building was completely restored in the 1980s with a bank becoming the major tenant on the ground floor. In 1997, the building was upgraded again to meet seismic safety standards without compromising the exterior façade.

110 E. Santa Fe Avenue

Listed: October 12, 1983

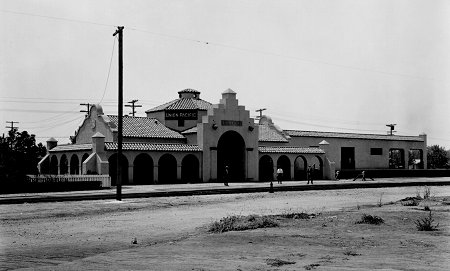

The Fullerton Union Pacific Railroad Depot was originally constructed at 109 W. Truslow Avenue on the opposite side of Harbor Boulevard from its current location. The Union Pacific Railroad was the third to lay tracks through Fullerton and to build a depot, which firmly established the city as the regional rail center for northern Orange County.

In addition to being prototypical of the depots for the Union Pacific Railroad from the early 1920s, the structure represents one of the six important examples of the Mission Revival style in Fullerton. The structure was composed of two sections - one for passengers and another for freight operations. By far the more decorative, the passenger section consisted of an eight-sided domed drum topped by an unusual round cupola. A Mission style parapet occurs at the two ends of the main gabled roof. An arched arcade with a Mission tile shed roof is situated on both sides of the main entry. The stepped parapet at the main entry is a deviation from the typical Union Pacific Depot design, offering an unusual combination of Zigzag Moderne and Mission Revival styles. The freight house section was a much simpler design with its flat-pitched gable roof supported by exposed wood trusses. A wooden loading platform once skirted both sides of this section of the building.

To avoid its demolition, the Redevelopment Agency successfully moved the building to its present site in 1980, and it was subsequently rehabilitated and converted for use as a sit down restaurant. Some additional construction was needed in this conversion, but all of the character-defining features of the structure's original architecture were retained.

Along with the Pacific Electric and Santa Fe rail lines, the Union Pacific Railroad played a major role in the development of the city. The tremendous growth in population and agriculture in north Orange County in the early 1900s attracted the Union Pacific Railroad to place a line through Orange County as part of the connection between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City. Its first attempt failed, primarily because of resistance from the Santa Fe Railroad; after World War I, the power and influence of the Santa Fe Railroad had diminished, and the Union Pacific Railroad finally obtained the right to establish its tract. The depot in Fullerton was built in 1923, and a competition with the Santa Fe Railroad commenced. In 1930, the Santa Fe Railroad demolished its old wood-framed structure and built its impressive Spanish Colonial Revival depot. The depots of the three rail lines remained active until the late 1970s.

The relocation and preservation of the Union Pacific Depot in 1980, brought all three historic depot buildings together as part of a planned transportation center, which has become a regional hub for a urban transit system.

120 E. Santa Fe Avenue

Listed: February 5, 1992

The present Santa Fe Depot replaced the original Victorian depot that was constructed in 1888, a year after the arrival of the railroad in Fullerton. Built slightly east of the old depot, this poured-in-place concrete structure is about 256 feet long (plus a 150-long covered platform), designed in a Spanish Colonial style. The building's long, low-profile shape appears as a composite of forms, each with distinct features, which are assembled in a linear fashion. Arches of varying profiles appear throughout the building, while the use of a staggered gable and shed roofs with Mission tile adds to the visual complexity of the whole. This style of architecture is fully developed, with a fanciful use of detailing, such as quatrefoil windows, wooden shutters, concrete grillwork and a Monterey style balcony.

By 1990, many minor alterations to the Depot had taken place. After the Fullerton Redevelopment Agency gained ownership of the property in 1991, the Depot was fully rehabilitated and major improvements to the station were undertaken. The restoration of the Depot included the removal of the exterior paint to reveal the original varicolored stucco finish for the walls, which have been repaired and preserved. Also, many of the original interior features of the main lobby, including the ticket counter, have been replicated or restored.

The Santa Fe Depot, along with the railroad, is directly linked to the city's historical development. The Amerige Brothers founded the city only after they were assured that the Santa Fe Railroad Company would build its new line through the land they wanted to buy. The first depot was constructed in 1888, as the town was being laid out, and the railroad tracts reached Fullerton the following year. The Amerige Brothers named their 490-acre platted townsite after George Fullerton, the manager of the the real estate subsidiary of the railroad, the Santa Fe Land Company.

Much larger than the original Victorian station, the 1930-vintage depot was symbolic of the growth of Fullerton during the first 30 years of the 20th century. Upon its completion in July 1930, the Fullerton Daily New Tribune wrote, "Modern in keeping with the aspect of the city which it serves, the new depot marks another milestone in the progress of the fastest growing city in Orange County. Its construction marks the recognition of Santa Fe officials of the size to which Fullerton has attained."

Since 1930, and particularly during the 1940s, the depot has been the first building people see when they arrive in Fullerton by train. The unique character of the building carries a lasting impression -- now a very favorable one for the city -- given its recent rehabilitation.

The Fullerton Station continues to function both as a freight and passenger depot, retaining a legacy of the city's historic beginnings as well as serving as a reminder that it was the basis for the city's growth in the early part of the twentieth century.

515 E. Chapman Avenue

Listed July 1, 1993

This magnificent structure is the finest example of residential Mission Revival architecture in Fullerton. This residence features unique detailing, and its prominent parapet, scalloped arched openings on the centered balcony, Egyptian-influenced columns and capitals, leaded and beveled glass windows, arched doorway and sidelights, bands of casement windows, and open porches with large cast concrete urns, distinguish the house like no other in Fullerton.

The house and a detached garage set back well over 200 feet from the street. A long, horse shoe-shaped driveway has been retained like its initial layout and provides a remarkable setting for the residence.

The two-story structure contains approximately 4,500 square feet including a basement. The original garage, located about 50 feet to the north of the house, is designed in the same style and materials. Like the house, red clay tiles cover a hipped roof and a parapet crowns the front fagade. Two types of cement brick were used for the house: a gray granite-faced cement brick for the first story and a white cement brick elsewhere. All of the brick were made on the property.

The interior has its original detailing and materials. Segmented arches, friezes, wood pilasters and cornice molding are character-defining features in the main rooms. Australian red gum and oak are used for woodwork and paneling in the house. The fireplace is built with dark shades of red and brown tile.

The house was built for John Hetebrink, a son of Henry Hetebrink who was one of the early settlers to the area. (The Hetebrink family is associated with two other significant properties, both of which are situated on what is is now the campus of C.S.U. Fullerton.) John Hetebrink became a successful farmer who made his own fortune in the tomato, walnut and citrus industries. This residence was once part of a 40-acre ranch north of Chapman Avenue where walnut and orange trees were propagated. The Hetebrinks were involved with many community activities, and the residence was often the site of meetings, events and parties.

Ownership of the property remains with the Hetebrink family, and it continues to be used as a residence.

The house is a unique example of the Craftsman tradition, which frequently worked with the Mission style. The exterior is completely intact, and the interior has seen few changes in its 85 years. The house and grounds truly retain the integrity of location, setting, design, workmanship and materials.

1731 N. Bradford Avenue

Listed: September 2, 1993

The two-story, 4,000-sq.-ft. Pierotti House is the finest example of Neo-Classical residential architecture in the Fullerton area. Designed by Charles Shattuck of Los Angeles, the redwood-sided house features a diversity of architectural elements. Prominent among these are two pairs of fluted Ionic columns made from redwood, which support a richly detailed pedimented portico. The front balcony extends to the north to form the top of the porte-cochere. Palladian-style fans accent some of the windows, and the variety of bays and window arrangements contributes to the appearance of intricate detailing. The interior features rosewood paneling, ceiling beams and cabinetwork. The house was built with a cellar that still contains a coal-fired furnace to heat the rooms above.

A portion of the gardens and orchard that were part of the original 40-acre ranch still surrounds the structure. As an important part of the overall character of the property, the grounds contain mature plantings, special garden areas, a sunken court, and some of the original orange trees planted by Mr. Pierotti.

Mr. Pierotti commissioned Charles Shattuck to design and supervise the construction of the house. Mr. Shattuck was a prominent architect from the Los Angeles area for over fifty years. He is noted for designing several large business structures in Los Angeles, including several country clubs, the city's first produce market, and its first mausoleum. While the Pierotti House was under construction, Mr. Shattuck traveled from Los Angeles at least once a week to the property to monitor personally the progress.

The Pierotti family was one of the earliest to settle in the Fullerton-Placentia area. Attilio Pierotti played a key role in the development of organized packing, shipping, and marketing of the citrus from the area. Born in Lucca, Italy in 1857, he came to the United States in 1874, and settled in Orange County two years later. By 1909, he had acquired 40 acres of land and had enjoyed enough success in the orange-growing business so that he was able to build his two-story house for his wife, Jane, and their four children. Mr. Pierotti was actively involved with the business affairs of the community for many years, and his wife promoted many cultural activities of the era. Their house was used frequently to entertain prominent local persons and friends from Los Angeles, where the family had social connections.

Although now nearly hidden from public view behind fencing and high shrubs, the house and grounds are an excellent example of the beautifully landscaped homes of Orange County's prominent orange ranchers who gained their fortunes from the late 1890s through the 1920s. Today, the remnant .9-acre property is still owned and used as a residence by the Pierotti family.

201 E. Chapman Avenue

Building Listed: September 30, 1993

Mural Listed: June 16, 2020

Designed by architect Carlton M. Winslow and constructed for $295,500 in 1930, the Fullerton Auditorium is an outstanding example of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture with Italian Renaissance design elements. The walls are poured-in-place concrete and the gable roof features red clay tiles. The imposing front fagade is symmetrical in design and richly decorated with Neo-classical motifs. A wide variety of cast concrete emblems embellish the classically shaped parapet, windows, and rectangular portico. The four story high tower is crowned with an octagonal dome clad in mosaic tile in rich shades of blue, gold, and green.

Just as outstanding is the interior workmanship and detailing. The large auditorium, which seats over 1,300 people, features an elaborate ceiling of painted and decorated rough-hewn beams, the original wrought iron chandeliers, arched side isles with composite capitals, and other classical ornamentation. In 1995, the building was fully rehabilitated and improved to meet seismic safety requirements. Additionally, the grand Wurlitzer Organ, original to the building, was restored and is in use today.

A 75-foot long, 15-foot high mural entitled "Pastoral California", painted by W.P.A. artist Charles Kassler in 1934, is found on the west side of the building under the arched arcade. A landmark in its own right, the mural is a true "fresco" - a medium rarely used for this type of artwork - that was totally restored through a community effort in 1997, after it had been covered by paint for 56 years. The mural was added to the National Register listing on February 28, 2022.

The building was orinially named for Louis E. Plummer, superintendent of Fullerton High School and Fullerton Junior College from 1919 to 1941. Mr. Plummer was highly involved in public educational activities, not only in in Fullerton but with organizations at the state and national level as well. Unfortunately, Mr. Plummer was allegedly involved in the Klu Klux Kaln in the 1920's. The Fullerton High School District Board of Directors voted to change the name of building to the Fullerton Auditorium on June 16, 2020.

Fullerton Auditorium was built in 1930, after several years of planning by the city's leading citizens. Since its construction the facility has been a center of entertainment for the community. Music organizations from both the high school and junior college have performed for social and civic groups. Not only do students gain their first experiences in drama, dance, and music there, the auditorium is used to stage important theatrical productions and community-oriented cultural programs. Throughout its 70-year history the auditorium has served the community well, giving Fullerton its fine reputation as a cultural and educational center for north Orange County.

In 2020, the Fullerton Joint Union High School District was awarded a grant of $3,434,000 from the state of California for seismic and handicapped access improvements to the Auditorium. The project started in January 2021; in addition to stabilizing the clock tower, an addition was required on the east side of the building to provide proper handicapped access to the auditorium seating and additional restrooms. These improvements were completed in November 2022.

122 N. Harbor Boulevard

Listed: April 19, 1994

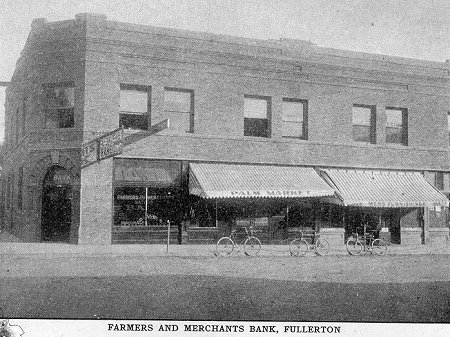

The Farmers and Merchants Bank building, initially constructed in 1904, received its beautifully detailed beaux-arts façade in 1922. Frank Benchley, a local architect, designed this embellishment. Accented with ornate classical motifs, this two-story building located on the southeast corner of Amerige Avenue and Harbor Boulevard is the only example of the Beaux-Arts style in Fullerton.

A dramatic diagonal corner entrance, crowned with a decorated parapet, provides the focus for the front (north and west) façades. The use of shields, recessed panels, faux stone, molded trim, and classical floral motifs provides the decoration for the exterior of these building sides. The façade of the first floor appears much as it did after the remodel in 1922. Glazed terra-cotta tile in a rich honey color forms the pilasters and cornice of the first floor. Light gray granite is used on the bulkhead below each window and at the bottom of the pilasters. When the building was extensively rehabilitated in 1989, the windows on the second floor were removed, and a wrought iron railing was installed between the openings. The floor plan of the second story was redesigned so that a perimeter corridor now provides the access to numerous tenant spaces. One difference may also be noted on the first floor: the building no longer has a central entrance at the south end along the west façade.

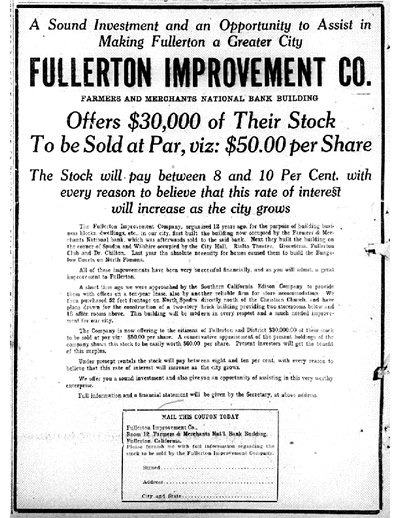

The Farmers and Merchants Bank - the forerunner to the Bank of Italy and later the Bank of America -- played a significant role in the economic development of the city. It was the first bank in Fullerton and was founded and continually managed by the area's most prominent citizens of this era: Charles C. Chapman, Attilio Pierotti, Samuel Kraemer, E. K. Benchley, August Tousseau and others. Indeed, there was a direct connection between the bank and the citrus industry. All of the men gained their fame and wealth with their involvement in the citrus and packing packing house industry, and all owned large ranches. The list of directors and officers of the bank were the same men who shaped the city during the first three decades of the 20th century.

After the Bank of America vacated the building in 1944, the Fullerton Music Company occupied it for over 40 years. The building was completely rehabilitated in 1989, when it was converted for use as a multi-tenant commercial building and given the name Landmark Plaza.

501 N. Harbor Boulevard

Listed: March 3, 1995

This building was the second Masonic Temple in Fullerton, taking the place of the much smaller facility at the northwest corner of Harbor Boulevard and Amerige Avenue. Rectangular in shape and three story (though multi-leveled) in height, it was constructed of hollow clay tile on a poured concrete foundation. Its Spanish Colonial Revival style is not ornate but is rather clean-lined and eclectic. For example, parts of the building have a flat roof with Mission Style parapets at the north and south sides. At the same time the front portico, with its elevated entrance, has a Neo-Classical treatment.

The east fagade is the primary elevation; it is symmetrical except for an extension at the south end. At the center is a pedimented portico that is supported by two columns with unadorned capitals, arrived at by a double set of stairs. Marble cornerstones are under each column, with the Masonic emblem and date of the building's construction etched in the north one.

There are other distinguishing architectural features: the uniform placement windows, the treatment of the upper balcony on the north side and the decorative roof rafters on all building elevations. The interior spaces, especially the main meeting room on the second level with its wood paneling and detailing, are equally important features. Frank Benchley, the son of Edward Benchley and a prominent local architect, designed the building.

he Masonic Temple was the first of the major buildings to be constructed in the prosperous decade following WWI. Construction lasted nearly a year, and the final cost totaled $115,000 for the structure and its fixtures. The groups that were associated with the Masons grew in the years following the building's completion, and for a time Fullerton had more lodges and chapters than any other community in Orange County.

As a social institution, Masonic membership was predominantly made up of high-status individuals and entrepreneurs - almost always men -- until the 1940s. The lodges were social groups that had ritualistic meetings, social events like dances and picnics, and game room activities. Other functions that attracted members included moral guidance, support groups, and charitable care for orphaned children and the elderly. The Fullerton Masonic Temple had all of these functions.

The Masonic Temple was the center of social activities and charitable events in Fullerton, particularly during the years before the advent of television. Many of the City's prominent men belonged to this organization, with membership remaining well over 400 until its decline starting in the 1950s. In 1993, with membership dropping below 200 and no money available for needed improvements to the building, the Masons sold the property. The current owner completely rehabilitated the building in 1995 - and in the process restored it exterior -- as part of a conversion for its use as a banquet hall and reception center.

117 N. Pomona Avenue

Listed: February 13, 2001

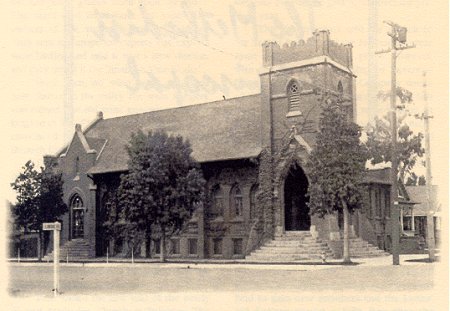

An impressive Gothic Revival structure, this masonry building is the oldest remaining church in Fullerton and has served the needs of three different congregations. The Methodists erected the church in 1909, at a cost of approximately $20,000. When the Methodists built their present church across the street in the late 1920s, they sold this property to the Seventh Day Adventist Church, which occupied the church until 1964. The Methodist Church took ownership a second time, with the intention of demolishing the building to use the property as a parking lot. That endeavor proved too expensive, so the property was again sold, this time to the First Church of Religious Science.

The church exhibits many features reflecting the New England roots and the British heritage of the Methodist minister who commissioned the construction of the building. The church is set close to the street, and a decorated three-story square tower caps its raised corner entry. Other defining features are the pointed arched windows and entryways, engaged buttresses, and the detailing with brickwork.

The reddish-brown brick used in the construction of this structure were handmade by the Simons Brick Company of Los Angeles. These distinctive bricks, each bearing the Simons stamp, are noted for their superior hardness and were used to construct innumerable Los Angeles-area institutional landmarks and residences. This structure is the only building in Fullerton built with bricks from the Simons Brick Company.

Many of the original Gothic-style appointments and decorative elements of the interior are intact. Among several stain glass windows throughout the church, two feature the use of opalescent glass, noted for its deep, rich coloring. These are the large 10' x 12' icon on the sanctuary's west side and the north-facing window that is composed of three separate stained glass arches.

The church's interior layout is based upon the auditorium-style Akron Plan. Although the Akron Plan had become the standard for the Methodist and other Christian denominations by the 1890s, this layout was not used in Fullerton until the construction of this church.

This structure was designed by famed Los Angeles architect Albert R. Walker. Walker designed many notable buildings in Los Angeles in the first half of the 20th century. The First Methodist Episcopal Church was one of Walker's first commissions and represents one of only a handful of structures that he designed before forming a series of partnerships with other architects.

Since its acquisition in 1967, the First Church of Religious Science has faithfully restored the building. In 1987, the Whittier Narrows earthquake caused extensive damage. Within three years the church completed the work to retrofit and repair the building at cost of over $500,000. The Northridge earthquake in 1993, however, again damaged the tall brick chimney on the west side of the building, and the decision was made not to rebuild it.

112 E. Commonwealth Avenue

Listed: April 26, 2002

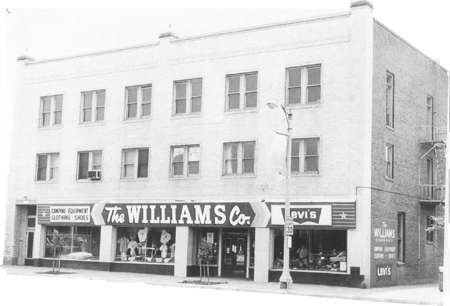

This imposing three-story brick structure was designed and built by Oliver S. Compton for the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Lodge #103, as evidenced by the 1927 cornerstone at the building's northwest corner. Designed from the start as a profit-making venture, the building was used as meeting and activity space for the Odd Fellows. Lodge members reserved the second floor for their exclusive use while leasing out the first floor for office and retail space and the third floor to other local patriotic and fraternal organizations. One of the first tenants on the ground floor was the United States Post Office. The original pressed tin ceiling, which graced the lobby of the Post Office, is still in place. A later use for the ground floor was a food locker, and since the 1950s, the Williams Company has occupied this space. The Odd Fellows Lodge occupied the upper level of the building in some capacity until 1949, and the structure continued to serve as a lodge and meeting room for various groups well into the 1970s, when occupancy was restricted to the ground level for safety reasons.

As a striking example of the brick commercial structures of the 1920s, the building's main decorative feature is the use of glazed, pale pink and blue terra-cotta tile across the street façade. It is the only building in Fullerton with this type of unique material. Three turban-shaped copper cupolas decorate the front edge of the building. A series of arched windows on the upper level of the west wall is also a key design feature. It is the interior space, however, that gives the building its architectural significance.

The upper level spaces are divided so as to provide assembly areas for both large and small gatherings, each with adjacent dining and kitchen facilities. There is a two-story high, 3,400-square-foot auditorium with pro-cenium stage and built-in seating along the walls. There is also a smaller, 2,000-square foot space, situated on a third level across the front of the building.

The building was extensively rehabilitated in 1994, and its front façade is now completely restored. In 1994, the work also included seismic retrofitting, where a steel framework was placed on the outside to brace the west wall. This alternative was chosen, because its placement was considered to have the least impact on the building's most important feature: its interior spaces and appearance.

In 2002, a new three-story lobby with a stairwell and elevator was added to the south side of the building. The addition is designed with brick veneer and detailing to complement the existing architecture, but it also exhibits features and forms to indicate clearly that it is not part of the building's original design. The addition now allows the upper levels of the building to be occupied again.

The long history of the building's use for public assembly has contributed broadly to the city's cultural development. It is the social history associated with the building - more so than its architecture - that is the property's legacy to the community.

237 W. Commonwealth Avenue

Listed: May 22, 2003

An exceptionally fine example of the Spanish Colonial Revival style applied to civic architecture, the former Fullerton City Hall, now the Police Station, was one of a number of Work Projects Administration (WPA) buildings completed in Fullerton in the 1930s and 1940s. The building was originally designed to house all city government offices and departments, including a jail, city council chambers, and a courtroom. At the time, Fullerton residents believed the City Hall would contain all the services the city would ever need.

Constructed in 1939-42 of poured concrete, the City Hall is a graceful, one and one-half story building with a basement that has an L-shaped plan opening toward the southwest. An unusual three-story clock tower is positioned at the central corner. The building's balanced design, enclosing a sunken patio on two sides, is complemented by fine detail work, including art deco tilework and decorative wrought ironwork. One of the premier tile companies of the era—Gladding, McBean and Company—produced all of the colorful and noteworthy ceramic and terra cotta tiles that decorate both the interior and exterior of the building.

The City Hall was designed by noted architect G(eorge) Stanley Wilson, a British immigrant who arrived with his parents and five siblings in Riverside in 1896. By the mid-1930s, Wilson had established himself as one of the premier exponents of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture, and he was a natural choice as an architect for a city that favored Spanish building designs. Wilson was at his artistic peak in the 1920s and 1930s, and the City Hall reflects the grace, harmony, and balance that his buildings had during this period. Wilson designed many buildings around Southern California, but is best known for his various projects from 1909 to 1944 for Riverside's famed Mission Inn. In 1909, Wilson began to work closely with the Inn's flamboyant owner Frank A. Miller (1857-1935) on small additions and changes to the building, which eventually became the largest Mission Revival building in California. Working under Pasadena architect Myron Hunt, Wilson was superintendent of construction on the Spanish wing, when the Spanish dining room, large kitchen, Spanish Art Gallery and its rooms above were constructed in 1913 and 1914. In 1929, Wilson designed the Inn's major addition, completed in 1931—the five-story structure on the northwest corner of the block, facing Sixth Street and Main Street. The wing included the International Rotunda, the Saint Francis Chapel, the Saint Francis Atrio, and the Galeria.

The City Hall houses a valuable treasure: a series of murals depicting Southern California history, which were painted by Helen Lundeberg (1908-1999), one of the leading female artists of the American west. Wilson commissioned Lundeberg in 1941 to paint a three-panel mural for what was then the city council chambers. Titled "The History of Southern California," the panorama of panels depicts early California history from the landing of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo at San Diego Bay in 1542 to the early days of the movie industry in Hollywood. In 1992-93, the murals, which had been painted over and obscured by a false ceiling when the Fullerton Police Department took over the building, were completely restored by ConservArt Associates at a cost of $80,000.

200 Brea Avenue

Listed: August 11, 2004

Hillcrest Park was placed on the National Register of Historic Places for both its historical importance to the development of the City of Fullerton and its distinctive landscape characteristics. Constructed on 35.6 acres, Hillcrest Park is the City's largest, most beautiful, and historically significant park. In January 1920, the City of Fullerton purchased 33.649 acres from Fred M. West for $67,298 for use as a park. Two acres of the property had been acquired earlier for a reservoir on September 8, 1913, and the remaining property was considered ideal for park purposes. At the time of the purchase, the property was vacant aside from a few wildflowers and barley fields. Two local businesses were using the parkland: Dean Hardware was storing a cache of dynamite in the hillside off Brea Boulevard, and Arthur W. Purdy was leasing land at the base of the hill off Lemon Avenue for his diary business. Fullerton had only 4,415 residents in 1920, but town boosters, who were primarily transplants from other areas of the nation, recognized that they were building a town and were eager to establish a park system. Then known as Reservoir Hill, the parkland property was selected because it would be a recognizable landmark from the northern approaches to the city. It was also envisioned as Fullerton's "great" park. The Fullerton Board of Trade was entrusted with naming the site, and after soliciting suggestions from the general public, the parkland was christened "Hillcrest Park" on May 19, 1920.

When the land for Hillcrest Park was purchased, Fullerton's park system was in its early development stage. The Park Commission, established in 1914, oversaw one city-owned park, Amerige (formerly Commonwealth) Park, and the library and grammar school grounds. Park planning progressed on a piecemeal basis until the Park Commission decided to hire a park superintendent. The Fullerton City Council instructed the City Clerk to advertise for the position on July 24, 1918, and Johann George Seupelt was hired as Fullerton's first park superintendent on October 18, 1918. Seupelt quickly developed plans for Amerige Park, and when the land for Hillcrest Park was purchased, began preliminary plans for what was to be Fullerton's largest park. By 1922, Seupelt had completed formalized plans for Hillcrest Park.

Bavarian-born Johann George Seupelt arrived in Baltimore in 1904. He served as a horticulture instructor at Washington State Agricultural College in Pullman from 1906 to 1908, then as Spokane's city forester from 1908 to 1915. During this time, he wrote articles on gardening and delivered speeches on tree planting and management. In 1908, Seupelt became the first student from Washington State Agricultural College to receive an M.S. in horticulture and landscape architecture. He became a United States citizen in 1909. In 1917, Seupelt moved to Los Angeles to assist the great California landscape architect Paul G. Thiene, who was then establishing a private practice. Born and educated in Germany, Thiene specialized in Italian and Spanish gardens of great size and intricate detail, most notably the grounds of the Doheny or Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills, now a public park. In October 1918, Seupelt accepted the position as Fullerton's first park superintendent. After assuming his position, Seupelt quickly implemented changes to Fullerton's park system. In November 1918, he completed plans for Amerige Park, which were immediately approved, and the park grounds were quickly developed. That same year, Seupelt began systematic tree planting in the city. Over 2,500 trees were planted at a cost of $4,883 throughout the city's thoroughfares. He completed plans for the grounds of Wilshire Avenue School (1914), Fullerton's second elementary school, which were implemented over the next two years. For his landscaping projects, Seupelt initially trucked in free plants and trees from Santa Ana and other nearby cities, but by 1920, he had established a nursery that provided many of the plants needed for public landscaping. He also continued to purchase plants and trees from local growers in Fullerton, Anaheim, and Placentia. After his services with the city were discontinued in 1925, Seupelt opened a landscaping business in downtown Fullerton (109 N. Spadra). While in Fullerton, Seupelt also completed landscaping plans for the Fullerton Hospital, the La Habra Women's Club, Whittier College, the Montebello City Park, and grammar schools in Anaheim, Brea, and Placentia. In addition, he designed four electric city signs for the Chamber of Commerce, which were placed at the principal gateways to Fullerton.

In 1926, Seupelt returned to Spokane where he worked privately and as the consultant landscape designer for the cities of Chewelah and Colfax, then as principal landscape designer for the architectural firm of Whitehouse and Price. Seupelt completed projects for Ernest V. Price and Harold C. Whitehouse, who designed hundreds of buildings throughout the northwest, until his death in 1961. His most significant project during this period was landscaping the Spokane Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist (1925-1954), an elaborate Gothic Revival church designed by Harold C. Whitehouse (1884-1974), and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Eminently qualified for horticulture and landscaping work, Seupelt was in the unfortunate position of being employed in government positions during World War I when anti-German sentiment was high. While living in Spokane, Seupelt was attacked by the editor of the Hunters Leader, a weekly newspaper published in Hunter, Washington, for being "un-American," and after moving to Fullerton in 1918, he experienced similar anti-German discrimination. Seupelt was reappointed as Fullerton's Park Superintendent on May 5, 1920, but in September 1921, a petition circulated calling for his dismissal. The Fullerton City Council dismissed the petition "owing to the fact that no charge or reason for such action was set forth," but when he was not reappointed in 1925, his German ancestry appeared to play a primary part.

Much of Hillcrest Park's distinctive look is due to work completed during the Great Depression.

Because many of the Park's visible elements, such as the fountain and road rockwork, were built by Work Projects Administration workers, much of the general information about the Park incorrectly assumes that the WPA was responsible for all of the Depression-era parkland improvements. In reality, Fullerton officials took full advantage of funding offered through a number of Depression-era programs: the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, Civil Works Administration, State Emergency Relief Administration, and the Work Projects Administration. Thousands of man hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars of relief funds were funneled into Hillcrest Park from 1931 to 1943, and it was the utilization of these monies that gives the Park its definitive character, shape, appearance, and feel. By the end of the Depression, relief workers had transformed Hillcrest Park into a truly unique environment, one with imaginative landscaping and a comprehensive and representative collection of leisure and recreational structures for the public. The transformation of the Park could only have been accomplished so extensively through the WPA and its predecessor agencies. At the time, money was scarce, but the ready availability of workers coupled with government public works projects served as an economic stimulant for the further development of Fullerton's finest park. The mass utilization of labor produced a public landscape that could not be recreated today, and Hillcrest Park stands as a legacy of New Deal and other work programs of the 1930s.

One of Hillcrest Park's most distinctive features is the flagstone that runs throughout the parkland. Aside from a row of flagstone pilasters constructed in 1934 in Amerige Park (1914), Fullerton's first city-owned park, this stonework is unique to Hillcrest Park. Flagstones of varying sizes and shapes are used in Hillcrest Park to pave and decorate walkways, stairs, benches, lawn and plant borders, walls, curbs, columns, pilasters, stoves, tables, barbecue pits, a fountain, and a bridge over a former lily pond. The stonework, which was used as an exterior finish over concrete, also delineates activity areas, creating separate spaces within the Park, and serves as a unifying element, providing design continuity throughout the parkland. The hand-crafted use of natural materials, common for WPA park construction, also lends a rustic and woodland feeling to the Park.

Rock work began with laborers hired by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, then continued with workers funded by the Civil Works Administration, the State Emergency Relief Administration, and the Work Projects Administration. Rock for these projects was quarried by city employees in Pomona and the Imperial Valley, then trucked to Fullerton. Fullerton officials relied on skilled rockmasons (assisted by helpers) to construct the stonework. Because New Deal programs were designed to put men to work, all the labor-intensive stonework was completed by hand from 1933 to 1941.

Hillcrest Park has two war monuments and three plaques that honor Fullerton servicemen killed during major wars fought in the 19th and 20th centuries. Since 1983, memorial services have been held annually on Veterans Day at the two monuments. The Park also has three distinctive buildings. The Hillcrest Recreation Center is the former American Legion Patriotic Hall, constructed in 1932 on land donated by the City of Fullerton in 1927. The other small recreation building off Lemon Avenue is the former Fullerton Boys and Girls Library (1927) that was moved to the Park in 1940. Located centrally in the Park is the Izaak Walton League Cabin. This rustic building, Fullerton's only cabin, is a reconstruction of a 1931 cabin that was destroyed by fire in December 1990.

510 N. Harbor Boulevard

Listed: October 25, 2006

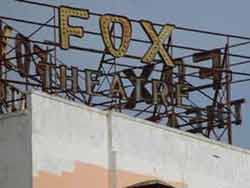

Located at one of Fullerton 's busiest intersections in the heart of the central business district, the Italian Renaissance-inspired Alician Court Theatre has been the dominant landmark in the City's historic downtown for over eighty years. Constructed in 1924-25 for $300,000 by local businessman C. Stanley Chapman, the son of Fullerton's first mayor, the mixed-use building was designed to function as a combination vaudeville/silent movie house flanked by a one-story retail unit on the south side with a two-story garden café on the north. The Theatre was Orange County's first movie palace, and the site of regularly scheduled film premiers. When it opened in May of 1925, the Theatre was the largest motion picture house in the County, representing the height of Hollywood glamour and sophistication. In 1929, a Spanish Colonial Revival super service station, designed by Stiles O. Clements of Morgan, Walls & Clements, was added to the south side of the building. In 1930, the Chapman family traded the Theatre Complex for a 940-acre ranch, and the building went through a series of names changes before finally becoming the Fox Fullerton Theatre, the name most popularly associated with the movie house.

The Fox Fullerton Theatre was constructed by the prestigious firm of Meyer & Holler, Inc. of Los Angeles , one of the most famous builders in movie theater history. At the time of the Fullerton Theatre's construction, Meyer & Holler, Inc. was the largest contracting firm in Los Angeles. In addition to its two best known buildings—the Egyptian and Chinese Theatres in Hollywood—the firm built movie studios and residences for many elite members of Southern California society, including Harry Chandler, Edward L. Doheny, Hal Roach, Samuel Goldwyn, Charlie Chaplin, and King Vidor. The Fox Fullerton Theatre is the only extant movie theater built by Meyer & Holler outside of Hollywood.

The Fox Fullerton Theatre was designed by noted architect Raymond McCormick Kennedy (1891-1976). During his lengthy employment with Meyer & Holler, Kennedy participated in the design of hundreds of projects, and was responsible for many notable buildings, including Grauman's Chinese Theatre, the Petroleum Building (714 West Olympic) for Edward L. Doheny, the Security Pacific Building (6777 Hollywood Blvd.), second only in height to the Los Angeles City Hall when it was built in 1927, the West Coast Theatre in Long Beach, and the Whittier City Hall. He was also one of a number of architects that worked on the Pentagon in Washington , D.C. The Fox Theatre is an outstanding example of Kennedy's handling of Italian baroque elements and is his only completed work in Orange County.

The Theatre's interior features six canvas murals on the history and development of California created by A. B. Heinsbergen and Company, one of the leading theatrical decorating firms of the period, and additional hand-stenciled murals and iconographic artwork by notable artist John Gabriel Beckman, who also designed the murals for the Chinese Theatre in Hollywood and the Avalon Casino on Santa Catalina Island. The artwork created by Heinsbergen and Beckman represents their major commissions in Orange County.

234-236 E. Wilshire Avenue

Listed: February 2, 2009

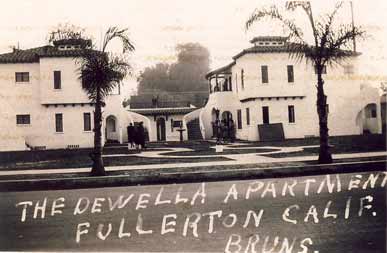

Lushly landscaped and well-designed, the Dewella Apartments, located at 234-236 East Wilshire Avenue , were constructed for $11,000 in the historic central core of Fullerton , California , in 1929. The Dewella is the only apartment or garden court apartment in the City of Fullerton . The complex is also the only time that the Spanish Colonial Revival style was applied to an apartment building in Fullerton . The Dewella's superb use of Spanish Colonial Revival architectural details—railings, gates, locksets for doors, weathervanes, lighting fixtures, decorative grills, etc.—provide a unifying theme for the complex, while also providing a counterpoint to the complex's large areas of white stucco.

One of the oldest apartment buildings in the city, the Dewella consists of eight five-room units arranged around a central courtyard that features an oval-shaped fountain. Two identical wings, extending north and south, are linked at the rear southern end of the lot by a one-story structure used for utility, storage, and garage space. The use of the two-story structures on the sides and a single-story structure at the rear is an unusual reversal of the bungalow court, the preferred multi-family dwelling in Fullerton prior to World War II. The Dewella Apartments are unique for their graceful combination of building and landscape, which features sweeping staircases, symmetrically designed apartment wings, and formal layout of the garden area in front. The exterior features white stucco walls, red tile roofs, clay tiles, decorative iron work, balconies, and other Spanish style elements. The Spanish Colonial Revival architecture integrates Mission-style turrets and Monterey-style balconies, a combination that is unique to Fullerton . Laid out in a symmetrical pattern, the Dewella's landscape and landscape elements (benches, fountain, pathways) are carefully integrated into the apartment complex's architectural design, enhancing its picturesque Spanish Revival ambience. The apartment court also features the oldest neon sign in Fullerton , only one of two that still remain within the original townsite. The apartments' identical interiors feature gas fireplaces, oak wood floors, built-in china and linen cabinets, coved living room ceilings, and hallway telephone stations.

The Dewella Apartments were constructed in 1929 by Herman Henry (1874-1966) and Edna H. Bruns (1888-1975) of Anaheim (1420 S. Los Angeles , razed). Herman Bruns, an engineer with the Southern Pacific Railroad, had moved out to Orange County from the Midwest around 1910. While Mr. and Mrs. Bruns lived in Anaheim , they had relatives, including Mrs. Bruns's father, living in Fullerton . The couple built the Dewella Apartments as a business investment. From 1910 to 1940, Fullerton had a serious "housing accommodation" problem and a "high demand for good rental property," and the city was seen as an ideal location for attracting renters. When completed, the Dewella Apartments cost Mr. and Mrs. Bruns $35,000: $11,000 for the complex and $24,000 for four lots. Mrs. Bruns spent an additional $1400 on furniture and other furnishings purchased from the Clausen Furniture Company in Santa Ana . All the units had matching furniture and rugs.

While Mr. Bruns provided construction funds for the Dewella Apartments, the project really belonged to Mrs. Bruns. She selected and worked with the building's designer/contractor Ora Vinton Noble, contacted the local press, decorated each of the units, and even sewed the draperies that hung in the windows of each apartment. The Dewella opened for public viewing and inspection on Sunday December 15, 1929, from 2:00 to 8:00 p.m., and the furnished eight five-room units were completely rented out in twenty-four hours. The Fullerton News Tribunefeatured the Apartments in a full-page spread and called the Dewella "One of the most artistic apartment houses in Orange County , yes, in Southern California ." The Apartment were described as having all modern conveniences, including "General Electric refrigerators, electric stoves, electric and gas heat, built-in cabinets and service porches." The furnished apartments were advertised as excellent accommodations for families with small children, not singles, but soon became a popular place for young married couples. Mrs. Bruns had made plans to erect two more identical units north along Wilshire Avenue, making the apartment complex the largest in Fullerton, but the Dewella unfortunately opened almost two months after Black Thursday, October 24, 1929, the day of the stock market crash, and construction of the additional wings was abandoned. The Bruns family held on to the Dewella Apartments until July 8, 1947, when they were sold to Mabel (1890-1982) and John Neuschafer (1889-1968), who resided in Apartment #1.

The Dewella Apartments were designed and built by general contractor Ora Vinton Noble (1882-1942), who, in turn, subcontracted out some of the work to local contractors. Noble was born in Albia , Iowa , on May 4, 1882, but moved to Santa Ana with family members around 1900. Throughout his lifetime, Noble held a number of jobs, but always fell back on his carpentry skills when the economy was bad. He was an automobile aficionado who would travel great distances to complete building projects at a time when roads were underdeveloped in the United States . He moved frequently, moving in and out of California , always using his residence as his business office. In 1908, Noble moved to Los Angeles ( 392 Budlong Ave. ) where he advertised himself as a carpenter, but by 1913, he had advanced to general contractor, making enough money to construct a seven-room Craftsman bungalow for himself at 1139 West 39 th Place.

Around 1914, Noble married Agnes Augusta McNeal (1884-1960), a member of the wealthy pioneer McNeal and Ross families, in Los Angeles . Agnes McNeal's grandfather was Jacob R. Ross, Sr. (1813-1870), the original owner of the property on which the City Santa Ana now stands. The couple moved back to Santa Ana and on June 20, 1914, Noble announced in the Southwest Contractor and Manufacturer that he had established himself as a contractor and builder at 1004 Baker Street , the home of his mother-in-law, Christiana McNeal (1853-1932).

In December 1916, Noble and his wife drove their six-cylinder Overland Light Six touring car 1,750 miles to Fort Worth , Texas , where he constructed a residence and later headed the service/used car department of the Overland Automobile Company headquarters in Dallas . The couple returned to Los Angeles in September 1917, settling in Long Beach (1157 Walnut) where Noble worked as a shipwright for the Los Angeles Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Company (later Todd Shipyards) in San Pedro during World War I. After the War, the Nobles moved back to Santa Ana (312 E. 3 rd St., 1019 Van Ness, 1615 W. 1 st St.) where Noble constructed a Young Women's Christian Association hut at Santa Ana High School in 1921 for $7337.19.

By the time of the Dewella Apartments' construction, Noble was back living in Long Beach (1145 Cherry Ave.), advertising himself as a "Contractor—Designer—Builder specializing in apartment house construction." After completing the Dewella Apartments in 1929, Noble worked on a project in Santa Barbara, moved out of California, but returned in the mid-1930s to Los Angeles (2232 S. Catalina, 1712 Reynier Ave.) where he remained until his death. At the time of his death due to heart failure on October 30, 1942, Noble was a cabinet maker. Ora and Agnes Noble, who had no children, are buried in the Ross Family section of the Santa Ana Cemetery (1919 E. Santa Clara), the cemetery founded by Jacob R. Ross, Sr. in 1870.

202 E. Commonwealth Avene

Listed: August 28, 2012

The Fullerton Post Office, a neat, attractive example of the Spanish Colonial Revival style applied to civic architecture, was one of a number of Depression-era government relief projects completed in Fullerton in the 1930s and 1940s. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 28, 2012 for both its architecture and interior mural. Although the building is often categorized incorrectly as a Works Project Administration (WPA) structure, it actually was designed by the United States Treasury Department's Office of the Supervising Architect. The Office of the Supervising Architect's plaque is positioned on the front of the building.

The Fullerton Post Office (202 East Commonwealth Avenue), the only federal building in Fullerton, was constructed in 1939. Situated on a 130- by 175-foot corner lot, the 6,000-square-foot Spanish Colonial Revival Post Office is a single-story reinforced concrete structure with a full basement. Spanish Colonial Revival design characteristics include an arched entryway, a low-pitched pantile roof (with two skylights), decorative iron work, and flat stuccoed surfaces. The building's stuccoed exterior, plastered in a flat, plain pattern, is painted off-white and the trim is a dark green. Basically rectangular-shaped, the structure faces north. Fireproof throughout, the interior is an example of the standard interior plans used by post offices during the 1930s. A relatively small portion of the interior is accessible to the general public; the bulk of the interior is devoted to the processing of mail by federal employees. Nearly all of the interior's design features are concentrated in the public areas, with the public space finishings of dark wood and terra-cotta wainscoting contrasting with the more functional and open arrangement of the workrooms where mail is processed.

Ten months after town founders George (1855-1947) and Edward Amerige (1857-1915) laid out the townsite of Fullerton, the federal government approved a post office for the small town, appointing Edmond E. Beazley (1863-1947) as the first postmaster on April 13, 1888. For the next fifty years, the post office, mirroring the growth of the community, moved to seven different locations in the downtown area. On May 22, 1888, the first post office opened in the Ford Grocery Store and shortly thereafter moved to the well-known Sterns & Goodman Grocery Store, both located in the Wilshire Building, situated on the corner of Spadra (now Harbor) Boulevard and Commonwealth Avenue. Total income for the first year was $242.31, and the postmaster's salary was $292.55. In 1892, William Starbuck (1864-1941), a druggist, took over as postmaster, and his store, the Gem Pharmacy, which moved three times during the next twenty-five years, became the new post office location. In 1889, Starbuck drove his horse and buggy to obtain the necessary 100 signatures needed to obtain free rural delivery of mail. Fullerton secured the first Rural Free Delivery (RFD) route in Orange County, and one of the first routes west of the Mississippi. By 1901, Fullerton's petroleum industry was booming, and a second RFD carrier, at $500 per year, was hired to service a 23-mile oil well route. Eventually, there were seven rural routes out of Fullerton. In 1913, hundreds of Fullerton residents put up mailboxes and free city delivery began with three deliveries daily in the business district and two in the residential district. Residents continued to receive mail twice a day until the 1980s. From 1917 to 1927, the post office was located in the Schumacher Building (212-216 N. Spadra), and from 1929 to 1939 on the first floor of the Fullerton Odd Fellows Temple (112 E. Commonwealth), now the Williams Building.

Fullerton's population grew from 4,415 in 1920 to 10,860 in 1930, and by the mid-1920s mail service and deliveries were increasing each year. From 1926 to 1929 alone, post office transactions had increased by twenty-seven percent, and it was obvious that leased space in the Odd Fellows Temple was no longer adequate. When federal relief building funds became available in 1930-31, the post office, along with a city hall and library, were at the top of Fullerton's request list. Rather than leased space inside a building, Fullerton residents wanted a separate postal building. United States Treasury officials granted building funds for the Fullerton post office in 1931, but the measure fell through in 1932 and again in 1933. Upset that the nearby cities of Anaheim and Orange had received post office appropriations, Fullerton residents

began to agitate for a postal building. Galvanized by an editorial in the November 15, 1933 Fullerton Daily News Tribune ("Why Not Fullerton?") that noted "Fullerton is one of the few cities of its size in California that has no post office building," the Fullerton Chamber of Commerce appealed to Republican Congressman Samuel L. Collins (1895-1965) to place Fullerton on the preferred list of federal post office projects, but that attempt failed in 1935. Undeterred, the Fullerton Chamber of Commerce spearheaded another post office drive in February 1936. Chamber head Harry F. Smith appointed a citizens' committee, chaired by Albert L. Foster (1898-1977), who again joined forces with Collins. On September 10, 1937, it was finally announced that Fullerton was approved for a new post office. The new structure would mark the first time that the community had a building erected exclusively for the purpose of being the post office, and its construction was closely watched by residents and local newspapers.

Fullerton residents wanted the new post office centrally located, near the railroad station, and preferably on a corner lot for easy access. All of those requirements were met when postal authorities authorized the purchase of two residences on the northwest corner of Pomona and Commonwealth Avenues for $19,000, and demolition began in 1938. When plans for the Post Office were completed by the Office of the Supervising Architect, bids for a contractor went out in February 1938, and San Diego resident George Goedhart (1901-1980) was the successful bidder at $54,950. The fixtures, furnishings and new equipment increased the building total to $91,000. Goedhart specialized in federal building construction and had already completed post offices in Colusa and Susanville (1938), California and Valentine, Nebraska (1936), and would go on to construct post offices in Buhl, Idaho (1939) and Lancaster, California (1941). Post offices constructed by Goedhart had standard floor plans and exterior designs that conformed to local or regional traditions.

Forty Fullerton laborers were hired, including Albert L. Foster, who won the excavation and sand and gravel contract. Construction began on April 3, 1939, and was completed in seven months. In a pageant-filled ceremony on June 3, 1939, Fullerton Masonic orders laid the cornerstone for the new building, and an equally elaborate dedication ceremony took place on October 28, 1939. On Friday November 19, 1939 at 1:00 p.m., postal workers closed their leased quarters in the nearby Odd Fellows Temple and moved into the new post office, half a block away, opening for business on Monday, November 20, 1939. In 1942, an oil and canvas mural ("Orange Pickers") painted by Paul Julian, was added to the interior of the post office. When completed, the Post Office and interior mural brought to the community a symbol of government efficiency, service, and culture. When the post office was constructed in 1939, Fullerton residents believed it would be the only post office the city would ever need, but by the 1960s, it was apparent that a larger postal facility was needed. The Commonwealth station served as Fullerton's main post office until 1962 when a larger building was leased at 1350 East Chapman.

In November 1941, Paul Julian, then one of Southern California best-known young artists, was commissioned by the U.S. Treasury Department Section of Fine Arts to create a mural for the Fullerton Post Office. Julian painted the 6- by 13-foot oil on canvas mural in the WPA Federal Arts Project studio in Los Angeles, and the mural was transported and installed in 1942. The Fullerton Post Office was not originally designed to accommodate public art so similar to other Class B and C post offices constructed during the Great Depression, the mural was positioned in the only spot available—the long narrow space above the postmaster's doorway. Julian's painting is one of three Depression-era murals in Fullerton, but unlike the other two—Charles Kassler's "Pastoral California" (1934) commissioned by the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and Helen Lundberg's "History of Southern California" (1941) funded by the Work Projects Administration Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP)—which were later painted or boarded over, then restored, the Julian mural has remained untouched and in excellent condition.

Titled "Orange Pickers," the mural depicts four young men and two young women picking oranges from two trees, then packing them into a wooden crate. One of the male figures on the left wears a sweatshirt bearing the letter "F" indicating that he is either a student at nearby Fullerton Union High School or Fullerton Junior College. Citrus crops were still the driving force of the Fullerton economy when the mural was painted, but the town's two other major industries—oil and aeronautics—are also depicted by two men working an oil well in the southwest (left) corner and a man, two airplanes, and a hangar in the northwest (right) corner.

Because of the small space available to Julian, the orange trees are positioned in the center of the mural so that the eye is first drawn to the middle of the painting, and then moves out to the rest of the picture. Fairly small in scale with a quiet composition, the mural is highlighted by color, particularly in the oranges and clothes of some of the pickers, which adds vibrancy to the painting. The mural employs a primary palate of green, brown, blue, red, and yellow. Similar to many government-sponsored murals, "Orange Pickers" presents an optimistic and reassuring view of the community at a time when Fullerton residents were suffering from severe economic stress. "Orange Pickers" is representative of the historically based, regional, illustrative realism that was funded under the Section of Fine Arts.

Although Fullerton residents have long enjoyed the mural's portrayal of community history, townspeople over the decades have also pointed out the inaccuracies of the painting's minor features. The ladder used is a step ladder, not the usual 3-foot wide and 15- to 18-foot tall straight ladder that allowed picking at the tops of the trees and simply leaned against a tree. Field boxes used to store oranges were shallower, heavier, and had grips on the ends to make stacking easier. Orange groves were not planted on flat land, but instead had furrows in rows among the trees for irrigation and to prevent runoff. Orange picking was dirty, scratchy work and workers wore long sleeves, hats, gloves, and boots, not the halter tops and short-sleeved shirts worn by pickers in the murals. The pickers are also Anglo at a time when most of the orange grove workers were of Mexican or Japanese descent.

Fans of the Fox Fullerton Theatre will frequently point out the building's connection with the Hollywood film industry, but the Fullerton Post Office on Commonwealth Avenue has an equally important link with the movie industry. The canvas mural on the west interior wall was painted by Paul Julian (1914-1995), a brilliant and seminal background artist for animated films. After Julian completed the post office mural in 1942, his last public art project, he went on to create layouts and backgrounds for dozens of Warner Brothers Pictures Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes cartoons, featuring such iconic characters as Bugs Bunny, Sylvester, Tweety Bird, Daffey Duck, Porky Pig, Yosemite Sam, and Elmer Fudd, while also working on several Columbia Pictures Mr. Magoo cartoons. When Warner Brothers began producing Road-Runner cartoons in 1949, it is Julian's voice that is making the distinctive "beep-beep" sound of the Road-Runner. Two of the animated films Julian helped to create at the United Production of America (UPA) Studio, The Tell-tale Heart and Rooty Toot Toot, were nominated for Oscars. When movie studios stopped producing cartoons, Julian moved into television and film, working on a number of television series, including Jonny Quest (1964-65), The Bugs Bunny Road Runner Hour (1968), Valley of the Dinosaurs(1974-75), The Sylvester and Tweety Show (1976), Dungeons and Dragons (1983), Alvin & the Chipmunks (1984), Mister T(1984), and Dragon's Lair (1984-85).

Born Paul Hull Husted, Paul Julian was born June 25, 1914 in Illinois. In 1920, Julian's mother, Esther (1893-1979), remarried a man named Frank Julian, and Paul and his brother Harry Husted took their stepfather's surname. The family moved to Santa Barbara (814 W. Valerio Street) in 1922. A child prodigy, Julian took night classes at the age of 13 at the Santa Barbara School of the Arts, studying with Belmore Brown, Charles Paine, and his mother, who had herself studied at the school. After his graduation from high school in 1933, Julian studied at the Chouinard Art Institute in Pasadena where he worked with Millard Sheets and Lawrence Brown as a scholarship student until 1936. That same year, he took first prize at the California State Fair, and in 1937, at the age of 25, he had his first formal exhibition in Santa Barbara where he showed the maritime paintings he had initially become known for along with more complex works.

After completing his education, Julian found that the economic conditions created by the Great Depression limited his artistic activities, and he turned to the Work Projects Administration Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP), a Depression-era welfare program for artists that ran from 1935 to 1943. Unlike established and significant artists of the period, such as Rockwell Kent, Thomas Hart Benton, and Maynard Dixon, who relied on federal relief aid for artistic survival, Julian used New Deal funding to establish himself as an artist. As a young artist, Julian was trying to gain a foothold in the art community while employed by the federal government, and the support and sponsorship he received from the WPA/FAP actually provided him with needed promotion and recognition. His first measure of success came from the public art shows where his work was displayed next to established artists and then from the recognition of his murals. He initially completed paintings for the Easel Unit, a number of which were purchased by schools and other institutions around Southern California. His WPA/FAP works were also featured in exhibitions, including the important Southern California Art Project Exhibition at the Los Angeles Museum in 1939, which featured major Southern California artists, and Frontiers of American Art, a national exhibition of the Federal Art Project at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco. These exhibitions, and the murals that followed, began to establish Julian as one of the foremost young artists in Southern California.

In July 1937, Julian received his first mural commission. He was hired to paint a mural at the Santa Barbara General Hospital, now the Santa Barbara County Psychiatric Health Facility, located at Calle Real and San Antonio Road. The mural ("Picnic on a Cliff"), in a large hall above three archways, depicts a group of young people enjoying a picnic. Created with oil pigments mixed with beeswax, which prevented the paint from drying with a gloss, the mural was based on Julian's boyhood memories of Santa Barbara. He also designed large, half-scale drawings for a mural at the National Guard Armory on East Canon Perdido Street in Santa Barbara, but lack of funding prevented their execution. Julian's last WPA/FAP work in Santa Barbara was an assignment from Buckley McGurrin on a project planned by Stanton MacDonald-Wright (1890-1973), who headed the Southern California Federal Arts Project. MacDonald-Wright was designing enormous tile decorations for the Santa Monica City Hall, and the work was sub-contracted out to several FAP artists. McGurrin assigned Julian a small parcel of decorative work using re-glazed tile, which Julian then turned over to others in Santa Barbara.

When WPA/FAP projects dried up in Santa Barbara, Julian moved to Los Angeles in 1939 (4957 Melrose Hill). His first assignment was to execute four 10- by 10.5-foot panels for a U-shaped courtyard on the exterior south wall of the new auditorium at the Upland Elementary School (605 5th Avenue). Using MacDonald-Wright's new petrochrome medium, the murals were created in a rented storefront with the help of seven or eight studio crew members, then transported to the school and hung. The four panels of the mural ("The History of Upland") feature separate scenes of Indians, padres, pioneers, and orange pickers. The outdoor mural, which is somewhat faded, but still in good condition, was made using 24 different colors of ground marble, as well as ground abalone shells, moonstones gathered at the beach, and petrified wood.